Reading games criticism – as separate from game reviews – is something I often find very frustrating. With some lovely exceptions, the feeling I often get when reading “games crit” could best be described as no-one is talking about the game itself.

For some time now, there has been a movement in games writing to get away from the kind of simplistic thinking that reduces games to numerical scores (“so that’s a 7/10, then?”) and engages with games on a deeper emotional and analytical level. As someone who’s been trying to make games with genuine artistic depth and significance since before the term “indie games” was popular, I’m obviously not opposed to this idea. Why then does it feel like this hasn’t worked at all, or works in a way that I find unsettling both as a player and as a writer/designer?

One could divide the type of writing I’m talking about into two general categories:

1) The Autobiographical Gaming Story. How Super Mario Helped Me Deal With My Parents’ Divorce, that kind of thing. A traumatic event, or sometimes a happy childhood memory, is somehow connected to a game.

2) A Modern Game Viewed Through An Autobiographical Lens. The author switches back and forth between narrating a personal event in their life (often of a sexual or relationship-related nature) and talking about the game, sometimes drawing parallels between the two.

Now, I should make it perfectly clear that there is nothing inherently wrong with either of these models. You can write perfectly meaningful things in this way, and no-one should be judged for employing these forms in and of themselves. However, there is one thing that tends to be lacking in these articles, and that is the game itself. Both forms can reveal a lot to us about the critic’s personal life and about the role of games in society – but this is autobiography and sociology, not art criticism. The game as authorial intent, as text, as work of art, is not examined. It is used a jumping-off point for other considerations – which, let me stress, may be perfectly legit – but it is not the primary subject of the analysis.

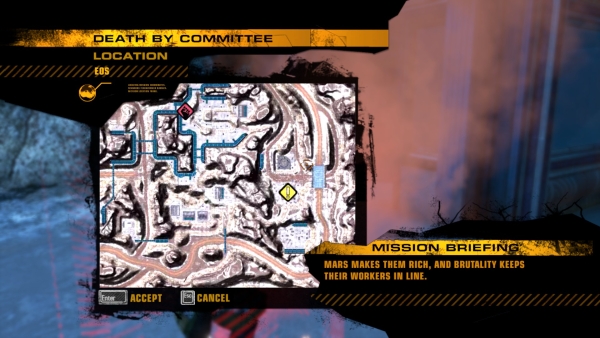

So we might get, for example, an article about how someone feels about the looting in Borderlands 2, but not an analysis of how the game juxtaposes the cities of Sanctuary and Opportunity as different models of human society, or how it explores the destruction of a planet for corporate profit, or how its primary villain is essentially a geek power fantasy laid bare. It’s not that it’s wrong to use Borderlands 2 to muse about your personal relationship with commercialism, or to write about how you played it when your grandmother died; it just tells us very little about the game itself, leaving the work of the game’s writers unappreciated.

Of course, this problem is hardly unique to games! We live in the age of “the personal is the political” and “academic writing could be seen as a kind of art.” Personal subjectivity is the highest value; our gazes are turned inwards, because that’s what is considered to be “deep” and artistic. And games are particularly susceptible to this, both in its benign form of people genuinely writing about personal issues they care about, and in the more exploitative form of “I can write anything and pass it off as meaningful,” because so many games are terminally vacuous.

But if we want to encourage works of higher artistic complexity, criticism must be more than autobiography and sociology. It has to amount to more than dismissing games for having too large a budget, or calling for a greater diversity of authors, or using games as a jumping-off point for essays on unrelated subjects. Criticism must engage with the games themselves – especially those that have something to offer. Take them seriously. Assume that there was an intent. Use the huge variety of intellectual tools available to the critic.

Even in so young and commercial an artform, you’d be surprised at how much there is to find.