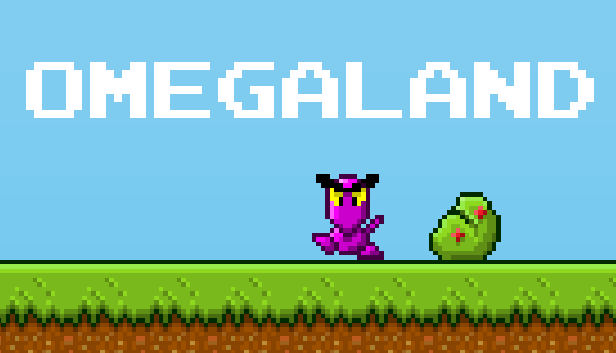

Years ago Michael Brough gave a talk in which he used the concept of working with or against a game’s grain. That idea, of thinking about game design in such physical terms – a game’s texture, grain, surface, shape – has fascinated me, particularly given my own thoughts about the centrality of structure to game narratives. This notion has been on my mind again lately, particularly with the release of Omegaland, a game that it would be fair to describe as deliberately rough around the edges.

Omegaland takes a great deal of inspiration from older games, but – despite what you might think at first glance – it’s not intended to look like Super Mario. If anything, it’s meant to look like a Super Mario clone. Let me explain.

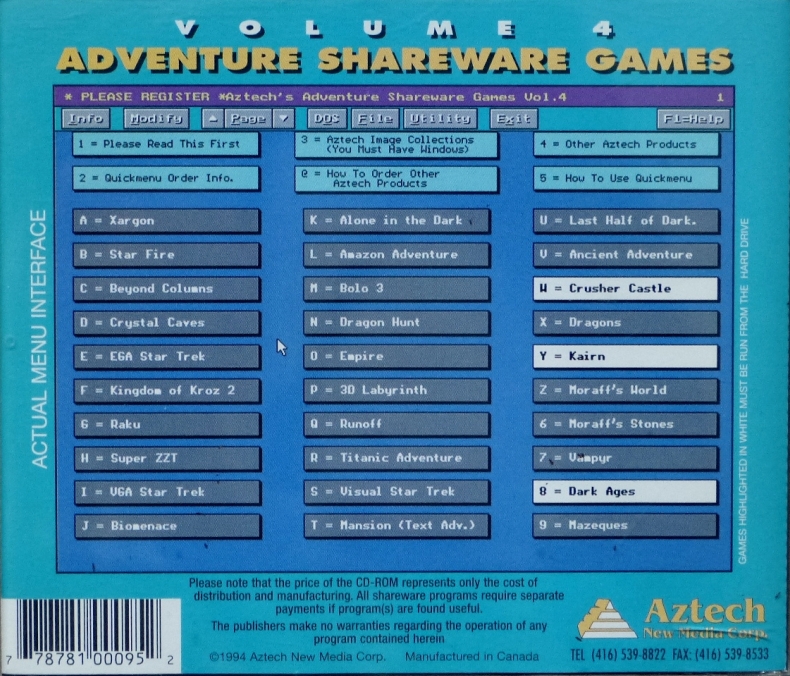

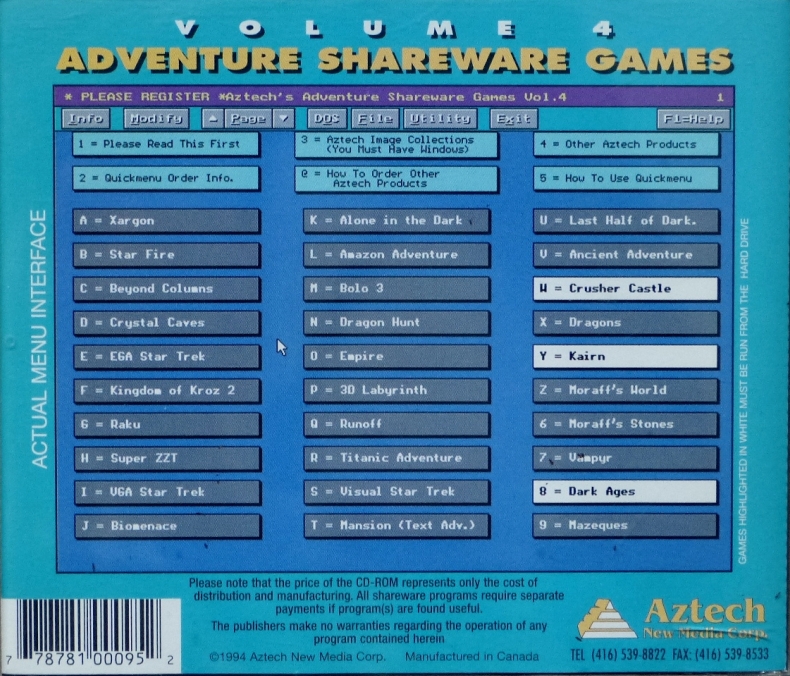

I’ve played a lot of strange little games over the years. When I was a kid, we weren’t exactly rich, and getting a new game was relatively rare. Computers were also evolving so rapidly at that point that even if you had the money, to play the latest games you needed the latest hardware. So I played a lot of freeware and shareware games. Some of them I got from the internet (waiting hours for a download that would take under a second now), but most I got from various collections of “5500 FREE GAMES!” and the like – or maybe from a CD burned by a friend, who’d gotten it from a cousin, who’d gotten it from a schoolmate, who’d… you get the picture.

I don’t remember a lot of these games very clearly. I was young, my language skills were limited, and half the time it was impossible to even get the games to run properly. So these games were a mystery to me – a mystery that grew in my mind, as I imagined all the great things surely hidden somewhere in there. These half-remembered games were one of the origins of The Sea Will Claim Everything, and they’re an even bigger influence on The Council of Crows.

There was this one game… sort of an adventure/RPG, where you moved from one static screen to the next by following the cardinal directions, and… I think there was a dragon in your village that you had to defeat? I also remember some kind of dwarf. You had stats to increase, and possibly objects to find. It was crude as hell, but somewhere – on the credits screen, maybe – there was a message from the people who’d made it, possibly also a low-res photo. And it made me realize – hold on, regular people made this. Which means I can make this. And I can make it better. The crudeness of it, in an odd way, made it easier to imagine making games of my own.

But where that game was genuinely crude, others were rough in a different sense. To go back to that idea of imagining games as physical objects, some of these games were absolutely brilliant in their own way, they simply had a different texture. You hear a lot of people talking about polish. Well, some works of art look best when polished. Other look best when the surface is left rough.

It’s very important to me that this not be taken dogmatically. Around the time indie games started being a “scene” (which was odd to me because I’d been making them for years), there were a lot of debates in which people took very extreme, inflexible positions that never made any sense to me. On the one hand you had the idea that games needed to be perfectly polished, that this was what distinguished the pros from the amateurs, and on the other you had people arguing that anything polished was bourgeois and the rougher a game, the more punk rock it was. Which is a bit like saying that all paintings should be painted the same way, all books should be written in the same voice, all music should sound the same. But different works of art have different requirements – that’s part of the fun!

There can, under the right conditions, be something magical about what seems to be an imperfection. The Lands of Dream games could never work without Verena’s graphics, because if they were more polished, the sheer weirdness of the world would feel incongruous. The flaws – which are deliberate, a result of making the graphics in this particular way – create an entirely different imaginary space than more polished graphics would. The metaphorical cracks in the material combine with the words to become tiny gateways to another world, where mushrooms can be communists and an object can smell of mathematics. To employ an overused and potentially pretentious term for a moment, the key here is the liminality created by a certain degree of “roughness” in the game’s design and presentation, which allows the game to evolve in strange and unexpected directions in ways that a more settled/consistent design and presentation do not allow.

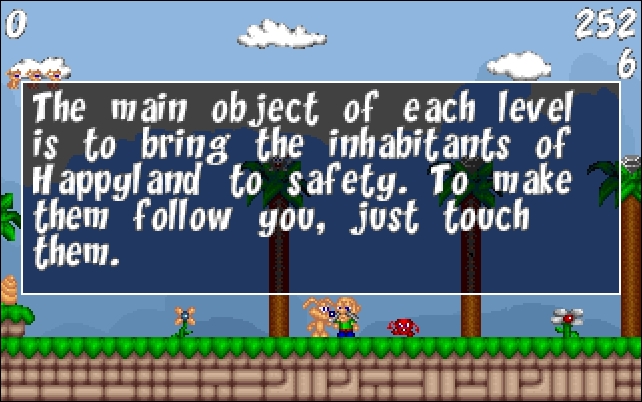

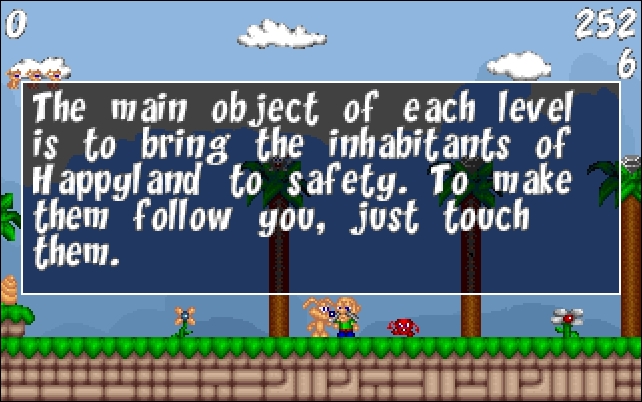

Thus, when working on Omegaland, I wasn’t mainly thinking about Super Mario, although Super Mario Land 2 was definitely an influence. Rather, I was thinking about the many odd little platform games I played over the years, some of them made long before indie games were a thing. (I wish I could remember all their names – I’ve searched and searched for some of them.) The very first version of Omegaland, in fact, used SpriteLib for its graphics – the same graphics used in HappyLand Adventures, a freeware game by Johan Peitz that I played to death in the early 2000s. The only reason I eventually asked Verena to make some graphics (“can you make graphics that will look like a cheap but enthusiastic Mario clone?”) was because the result felt too much like I was stealing from Johan’s game.

When approached as an artistic tool rather than as dogmatic prescription, considering a game’s texture – whether rough or polished – opens up a range of possibilities in the kind of experiences we can create. Personally, I find this exhilarating, and I’m lucky enough to be able to explore both ends of the spectrum via my own games and the games I make with other people. I’m amazed by some of the breathtakingly beautiful, aesthetically superb games people are producing. There’s nothing wrong with those. But sometimes I do miss the weird, janky games of the past and their strange sense of possibility.

I think this is another reason that a broader, more inclusive awareness of the history of the medium is invaluable to us as artists. Instead of looking only to the handful of landmark games that have been mythologized as the games that defined the medium, we should always be willing to check out the weird, flawed, fascinating games people have been making for decades. Art isn’t about a linear evolution from primitive to complex forms – it’s actually a tree with thousands of branches, rich for the picking.

Caution, though: some of the fruit is hallucinogenic.

Notes

- Of course, it’s essential that we differentiate between doing something badly or screwing something up (which happens to me all the time) and deliberately trying to create a rougher texture. A bug is still a bug.

- I could have called this “Ludic Texture and Liminal Spaces” but then I would die of embarrassment.