We’ve been playing Terraria.

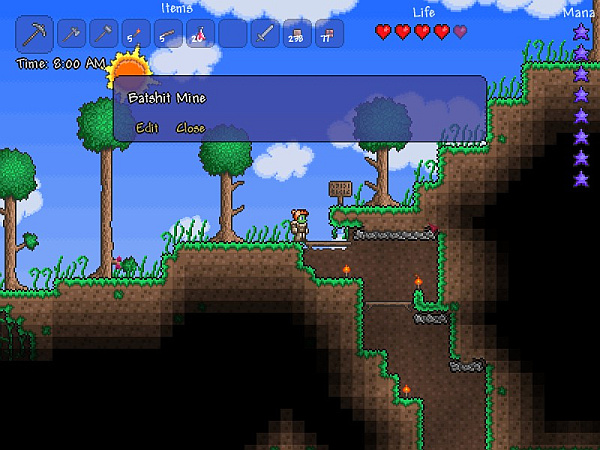

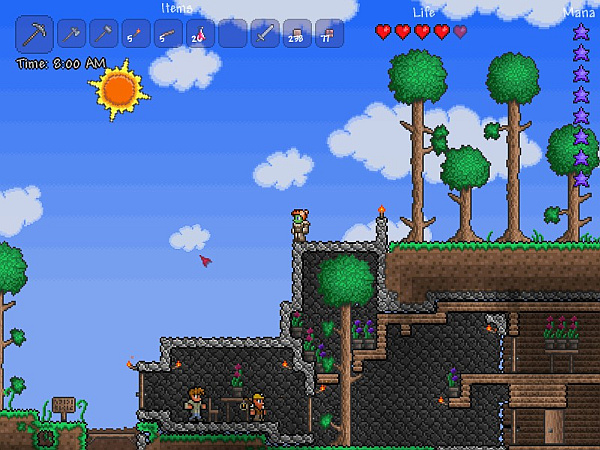

No, wait, let me rephrase that. We’ve been living Terraria. We’ve been digging mines, building towers, planting forests, crafting items, constructing absurdly long skybridges with gardens on them and finding new ways of fighting corruption, all with a remarkable amount of obsession. Oh, we’re still managing to work, we’re even watching the occasional episode of Buffy or Angel or The Elephant Man and His Magic Box, but Terraria is rather high on our list of things to think about.

If you haven’t heard about Terraria, it’s a… umm, well, a 2D exploration/platforming/building/action/sandbox game. A lot of people compare it to Minecraft, but my impression is that it’s more focused than Minecraft – more game than sandbox, one might say. Like Zelda had a child with Spelunky and Minecraft was the eccentric uncle who gave the child its first Lego. Is that weird? Yes, I think so.

Anyway, it will remind people of Minecraft, but it’s not a clone. I’m not a Minecraft expert, but that’s what I think. Terraria is Terraria.

It has an excellent balance between the abstract (the world is random, the player can modify just about everything) and the specific (certain locations always exist, certain goals must be accomplished to make progress, NPCs are not random). It also looks great and plays very smoothly.

I’m helpless against the power of such a game, really. A game that combines exploration and building speaks to all those civilization-building instincts that our species possesses, and I find the exercise of those instincts to be highly pleasurable. (You may be able to detect elements of this is Phenomenon 32.) There is something intensely beautiful about saying “We built this.” Games like Terraria can reach something inside us which is absolutely central to our entire history and philosophy. That’s why we’re here, you and me and everybody else. We’re here because we build.

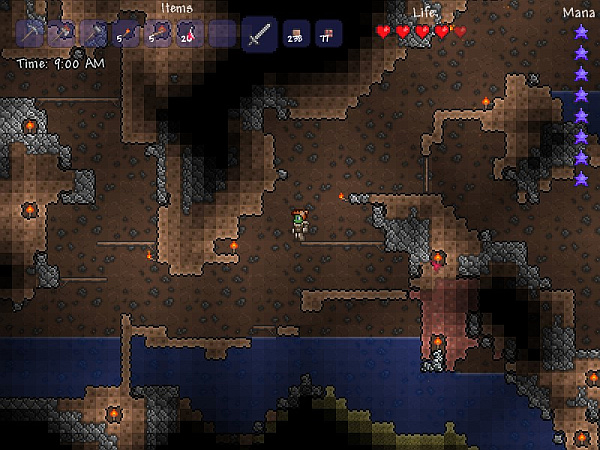

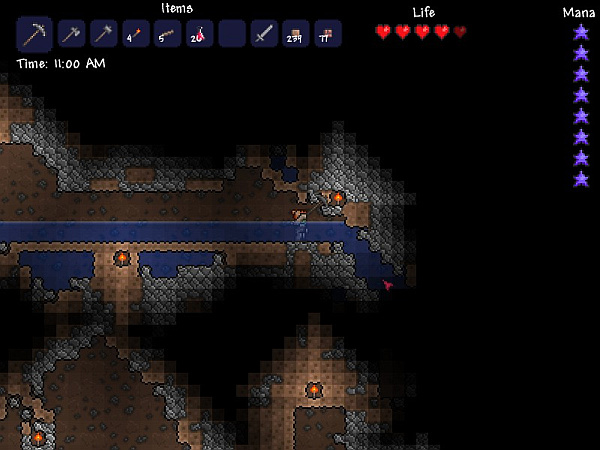

Equally exciting, and equally human, is the desire to explore. This is also great fun in Terraria – from discovering an underground chamber or a rare mineral to finding a whole new biome, the thrill of exploration is more powerfully evoked by this tiny little game than by most big-budget games I’ve recently played (one exception being Two Worlds II). Here, too, the combination of the abstract and the specific is just right.

I paid 10€ for this game, and I’ve already gotten more out of it than I’ve gotten out of games that cost five times as much. And the patches have all added nice stuff – where with most games the patches just fix shit that should never have been broken in the first place, here they add delightful new features that weren’t missing, but do expand the game’s scope. I know other games have done this too, but it’s worth noting, because it’s a very pleasant experience.

I don’t subscribe to the notion that procedural generation is the future. But games like Terraria show us that it is a tool that can be correctly employed by a designer to create a really good game, without sacrificing its artistic character.

I would love to see Terraria evolve until it has reached the complexity of a game I feel it is closely related to: Ancient Domains of Mystery, the greatest of the roguelikes. And I’d love to see more developers play with this model, with the mixture of design and randomness, of specificity and abstraction. It’s not the only way to go – I just as badly want people to pay more attention to storytelling of a more traditional sort – but I can imagine many great games being made that way.

Hell, I’d love to make one myself. But making something like this takes a talent that I really don’t have: advanced programming. So for now I’ll continue down my path of extreme specificity; a world created entirely by hand has its own advantages, after all.

For now, if you’re looking for something fun to play, I greatly recommend Terraria.