2013 was a weird year. I didn’t release a single game. But I worked. I worked unbelievably hard. I wrote and designed and programmed and squingled and boingled and frummed. And it’s all really awesome stuff, too, big promising projects that in many ways are unlike my previous work. Some of them are even so secret that I’m not allowed to tell you about them. (Seriously.) I’ll be releasing stuff nonstop next year. It’ll be madness. You won’t be able to keep up. It may start raining goats.

I’m in a strange place when it comes to games, though. As my toolset for making games grows, I keep experiencing these amazing moments of inspiration, much like when I first thought about making games. I’m more excited about the possibilities than I’ve ever been. Simultaneously, though, I’m about as disenchanted with the games “scene” as you can possibly be. It often feels like there’s absolutely no point in making games with any kind of artistic or intellectual ambition; when critics say that games need to evolve to a higher level of storytelling, they mean the level of a mediocre TV series. If you go beyond that, they won’t even recognize it. There are a few exceptions, and I’m glad they exist, but I can think of no other medium where there is such a catastrophic lack of critical depth. (I think it’s mostly due to the cultural isolation of video games from other art forms.)

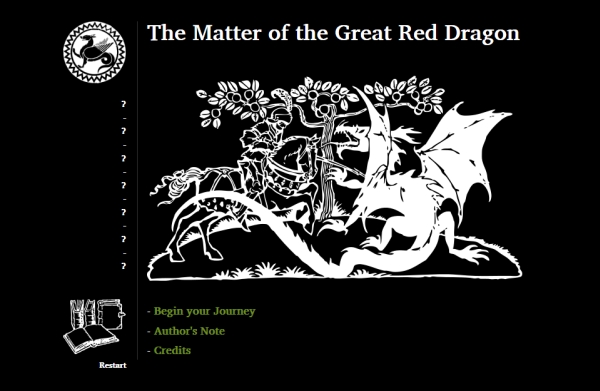

Anyway, as a result of that, there are some projects that I’ve decided aren’t worth making as games. They were stories where I was on the brink, undecided as to whether they’d be better as games or in some other form, and I’ve come to the conclusion that making games feels too much like screaming into a void. To start new game projects with the intellectual and artistic complexity of the Lands of Dream would feel like too much of a waste. So I just want to finish what I started, make those games that I feel have a chance, and then stop. Or maybe semi-retire, focus mainly on writing for other people and making a game of my own every few years. Something like that. 2014 will bring a veritable explosion of games, including Ithaka of the Clouds. That explosion may continue into 2015. But not too long after that I’m going to be done. 2013 made the necessity of that very clear to me: I can’t keep making games for the rest of my life. I never wanted to. At least not as my primary occupation. I’m a writer, and I need to write.

Speaking of Ithaka of the Clouds, the crowdfunding campaign was one of the biggest things that happened to me this year. It was great to see that while the Lands of Dream may not have a huge audience, they do have a very real and very dedicated audience. It was not only gratifying, but also immensely helpful – thanks to the crowdfunding campaign (and Verena’s tireless work), our finances have gone from Argh to Surviving, which is a pretty big deal. And I can’t wait to show you Ithaka. It’s still a few months away, but it will have been worth it.

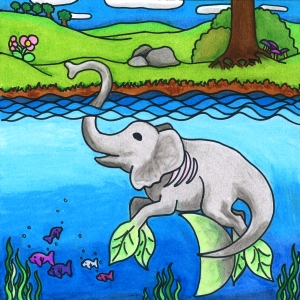

Less financially lucrative, but also thoroughly important, was the release of our children’s book, Στη σκιά του Αόρατου Βασιλιά (In the Shadow of the Invisible King). Perispomeni Publications did a great job producing the book, and the reaction has been magnificent. It hasn’t reached as many people as it might have a few years ago – people in Greece are desperately poor, and due to its size and quality the book is quite expensive – but the people who did buy it loved it. And not just parents, either! Verena and I have always said that people underestimate children, and I’m glad we were right about that. Children weren’t scared of the dark parts of the book, weren’t freaked out by the weirder ideas, and weren’t confused by the book’s political and philosophical contents. After all, all of those are the ingredients of a good adventure story, and that’s what we wanted the book to feel like: an adventure. (I know, I know. Translations. Looking into it.)

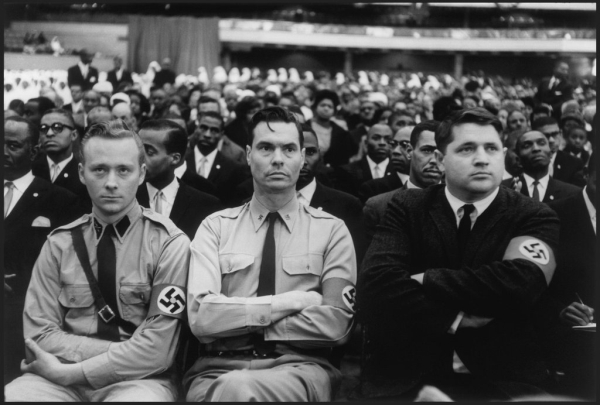

2013 was also the year in which I became persona non grata to a section of the indie games scene that I used to have a fair amount of contact with. In hindsight, I’m not particularly surprised that happened; the ideology of that particular group of people is so prone not only to fragmentation, but to the personal demonization of dissenters, that it makes the communist Left look like one big happy family. It was my article Would You Kindly Not that started the avalanche, but I realize now that the pressure had been building for some time, and I was getting increasingly uncomfortable with the reinforcement of most thoroughly racist and sexist ideas. I’m sorry for these harsh words, since I think a lot of the people involved aren’t aware of how shockingly imperialist, capitalist and US-centric their views are, but it got to a point where I could not live with myself if I didn’t speak up. Perhaps it would have been wiser to simply cut off all contact immediately, but at the time I hadn’t fully realized just how deeply these problems went, and I was under the impression that a culture of open debate was something most people on the Left desired. Now I know that, for the most part, American “anarchism” is not that closely related to the international kind, being more of a warmed-up liberalism, or even neoliberalism.

It’s depressing to think that even in 2013, the most radical perspective one could take of human beings is that they’re all equal. Hobsbawm may have had his issues, but this quote still sums it all up for me:

So what does identity politics have to do with the Left? Let me state firmly what should not need restating. The political project of the Left is universalist: it is for all human beings. However we interpret the words, it isn’t liberty for shareholders or blacks, but for everybody. It isn’t equality for all members of the Garrick Club or the handicapped, but for everybody. It is not fraternity only for old Etonians or gays, but for everybody. And identity politics is essentially not for everybody but for the members of a specific group only. This is perfectly evident in the case of ethnic or nationalist movements. Zionist Jewish nationalism, whether we sympathize with it or not, is exclusively about Jews, and hang — or rather bomb — the rest. All nationalisms are. The nationalist claim that they are for everyone’s right to self-determination is bogus.

– Eric Hobsbawm, Identity Politics and the Left

I can’t say the fallout from writing Would You Kindly Not didn’t affect me. I think what bothered me most were the personal attacks – not the political disagreement, but the sudden attacks on my character and the character of my friends, especially coming from people I’d always supported. I’m talking about shameful, outrageous slander against people who’ve never stood for anything other than equality and freedom. (And by the way, why isn’t it outrageous to accuse others of causing suicides, but controversial to say it’s not OK to judge others by their ethnicity?) By now I realize that this is how the entire “social justice movement” functions, but at the time the viciousness and childishness of it all was a little shocking. I was also depressed by the sheer number of people belonging to groups that one might categorize as oppressed who wrote to me saying “I’m X, I agree with or don’t have a problem with what you’re saying, I think the reaction is horrible, but I can’t say something in public because I’m afraid of being bullied.” And I don’t even blame them – look at how the people who did speak up were treated!

It’s mostly behind me now, or at least I hope so. I’m still writing about political theory, so identity politics does naturally crop up, but I try not to mention any names, and I block anyone involved with bullying tactics on Twitter. Occasionally someone will have a moment of self-righteousness about how evil I am (opposed to justice, not wanting people to have bodily autonomy, other things that completely oppose anything I’ve ever said), but generally they’re too busy hating each other, and I fully understand now how pointless it is to argue with people who thrive on outrage. If this is their niche, and this is how they make a name and an income for themselves, fine. I wish them no harm. But I’m glad they’re out of my life, even if I am now a “controversial” person who is less likely to receive support from the community.

On a much happier note, 2013 was also a year in which I made several new friends, partially out of this controversy; it’s inspiring to discover that there are people in every part of this world who don’t fall for the neosegregationist propaganda, who enjoy art that engages with the world out there and not just with the distorted images in the mirror and the invisible lines that divide us; people who give me hope that the hateful voices are just a very loud minority. I am really grateful for having met you all, and for the continuing friendship of many others. I know you all struggle with the inanity and insanity of the modern world as much as I do, so I’m deeply thankful for your kindness, your support, and your terrible jokes. Don’t give up, comrades! The revolution is coming any century now.

Finally, Verena remains the cute octopus that holds together my raft of log-shaped dream metaphors. I wouldn’t get anything done without her. Well, I would, but I would probably drown in the process, and then who would get up in the middle on the night to let the cat in? Ghosts would, yes, but then there would be ghosts everywhere, and you know how they are. So I’m glad we’re all still alive and healthy, more or less. Especially the cat. She’s the best.

And so I’ll end on that hopeful note, without dwelling on all the other unpleasant stuff.

Watch out for the koalas.